The Open Spaces of Toronto: A Classification

Brown + Storey Architects Inc. were commissioned by the City of Toronto in 1991 to produce a typological classification of public open spaces in the downtown core. ‘The Open Spaces of Toronto – A Classification’ encompasses:

- developing definitions and criteria for each of seven types of open spaces by examining examples in detail in Toronto’s downtown core;

- comparing these types to international examples drawn from local cities, North America, and internationally;

- suggesting principles for the planning and design of individual sites for public space; and

- recognizing networks and patterns of open spaces, and discovering ways of strengthening the existing systems.

The types of spaces documented and analyzed included forecourts, courtyards, linear parks, urban parks, squares, plazas, and metropolitan parks. The examples ranged from the natural environments of the Balfour Ravine to the very urban landscape of Nathan Philips Square and the Toronto Dominion Plaza, and from the large scale of urban parks like the Grange and Queen’s Park to small urban places like the Toronto Sculpture Garden. This study formed the background for guidelines for the creation and renovation of public open spaces in Toronto’s official plan.

Each type of open spaces are generally defined in terms of adjacencies/ edges, form and vegetation, scale, facilities/ use, and their ability to form systems of open space in the city. Several local examples are documented and analyzed to show a range of scales or variations of the open space type. Hard data is provided like ownership, depth, edge uses and hard to soft surface ratios; drawings illustrate the larger context of the space, a volumetric, elevation, section, private and public domains, and a detail plan.

The local examples are then compared to similar types outside of Toronto, in small towns, and abroad in terms of area, detail plans and sections, interior and edge elements and day/ night conditions. The following observations and principles are given according to three categories: Place Creation and Modification (the size and location), Place Definition (the design of edges), and Place of Possibilities (the internal ordering of the park design).

Excerpts from the report are featured below.

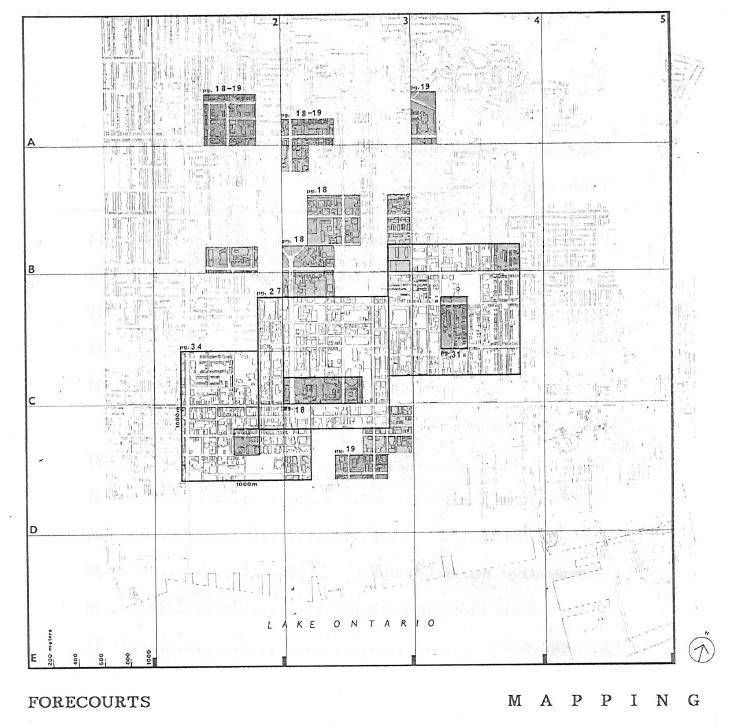

Forecourts

Definition: the open space between the public sidewalk and the main entrance of a building.

Location: In front of residential, commercial, institutional, and public buildings

Size: As long as the building or property face. Depth varies.

Landscape: to be specifically designed as either an extension of the building or as an extension of the public sidewalk.

Use: Entrance to building, casual sitting, passing by

System: Can collectively form a continuous open space along the street face and form incremental links to larger open spaces

Other: Open access at all times

Examples: Old City Hall, 311 Jarvis Courthouse

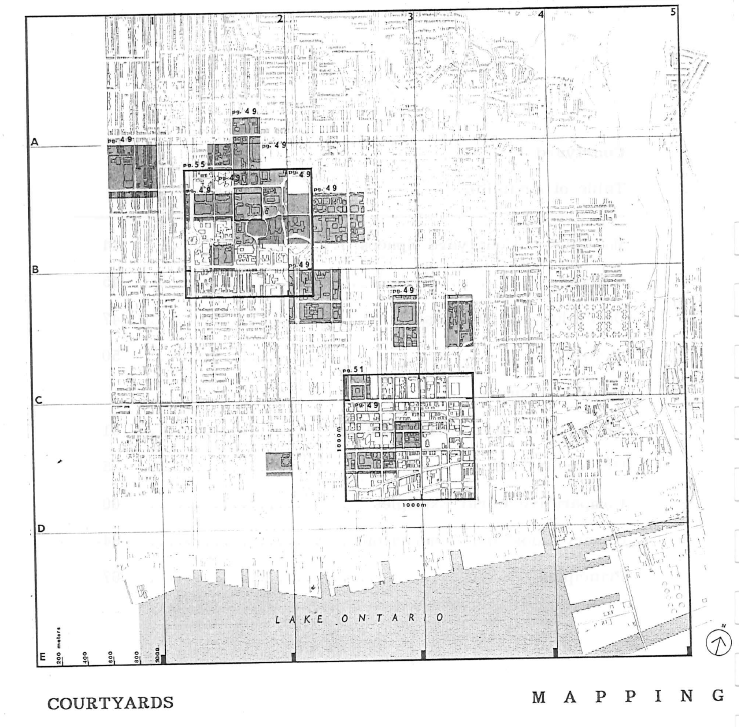

Courtyards

Definition: an open space substantially enclosed on all of its four sides by built form.

Location: interiors of city block with or without street frontage. It should always be well connected to public movement systems and avoid dead ends and isolated locations.

Size: size should be determined by the height of the surrounding buildings to ensure that the space receives sunlight.

Landscape: the organization of the courtyard should provide at least two clear public accesses. The courtyard should be designed as an enclose room with its own specific balance of paved and planted areas.

Use: playgrounds, cafes, casual sitting

System: courtyards can connect to public streets and form part of a continuous pedestrian system of movement

Other: avoid dead end courtyards and close courtyards after user hours if not in a regular public route.

Examples: University College courtyard, Ryerson University Quad

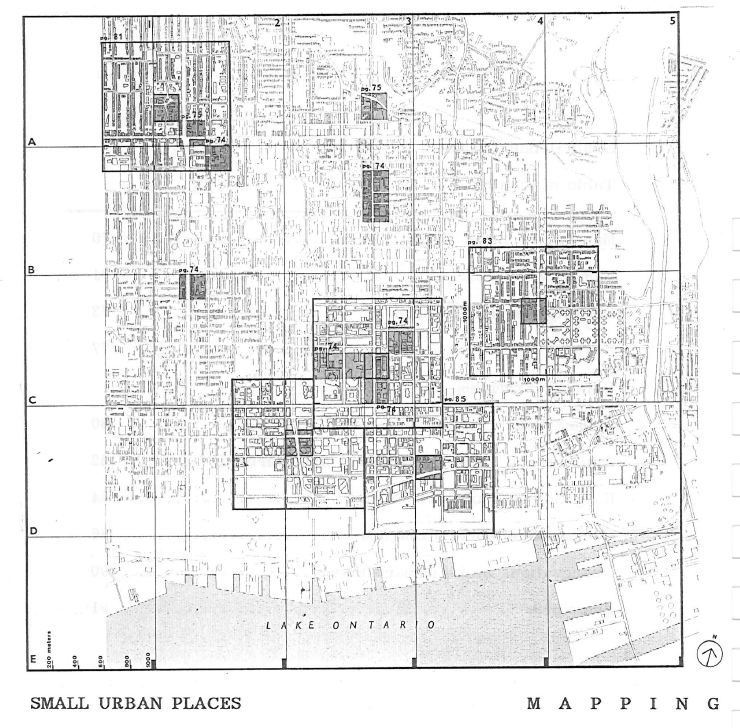

Small Urban Places

Definition: an open space that occupies an area that is less than a city block, and whose proportions are comparable to a normal building lot in the city.

Location: within a normal city block with a minimum of one side open to a public street.

Size: proportioned to a normal city lot; width to length ratio approximately 2:3.

Use: Eating lunch, playgrounds, ceremonies, performances, exhibitions, casual use.

System: The small lot park can be a connected link between larger urban park spaces and can also form part of a secondary pedestrian movement route through the city.

Other: Open to the public during user hours. The design should not create dead end spaces or places to hide. Lighting, access to public washrooms, and a public use at the ground floor of adjacent buildings ensure overlook and occupation of the site.

Examples: Toronto Sculpture Garden, Anniversary Park

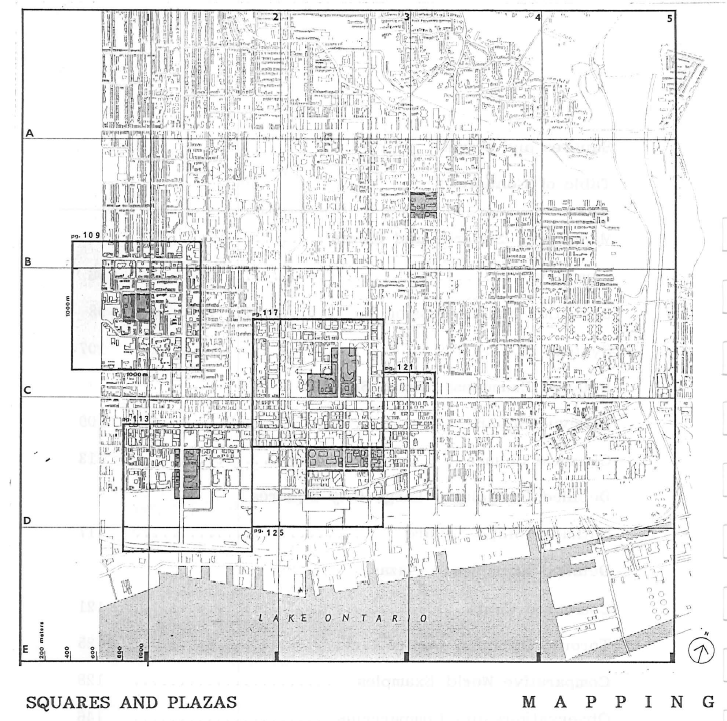

Squares and Plazas

Squares

Definition: a large public open space that occupies a large proportion of the entire area of a city block. It is surrounded on at least three of its four sides by public streets.

Location: the square forms a focus for its surrounding context beyond its immediate built edges. It is either surrounded on all sides by public streets or shares its block with a major institutional building.

Size: the size of the square depends upon the size of the block it occupies in the grid pattern. Squares located in the downtown core are larger than neighbourhood squares that occupy the smaller blocks found in residential street patterns.

Use: secondary pedestrian routes, eating lunch, entrances to surrounding institutions, public demonstrations, celebrations, ceremonies, performances and exhibitions.

System: the square forms a centre of a network of open spaces. Connections should be made with the square by smaller types of open spaces like forecourts, courtyards and passages, pocket parks, and by the geometry of paths and through routes.

Other: open day and night; provide high levels of lighting, on-grade public uses that are occupied at night, keep edges open and accessible.

Examples: Nathan Phillips Square, Clarence Square

Plazas

Definition: a rectangular open space that occupies a large proportion of or the entire area of a city block. At least two buildings are located within the limits of the site that create a series of connected smaller open spaces.

Location: The plaza is located on city blocks in the commercial core, with a minimum of one edge facing a public street.

Size: the overall size of the plaza ensemble is rectangular and occupies a major proportion of a large city block.

Use: casual use, passing through, eating lunch, secondary pedestrian routes, entrances to surrounding buildings, small performances and exhibits.

System: the plaza can connect into other secondary routes across city blocks, and work within a system of consistent setbacks.

Other: open day and night; provide high levels of lighting, on-grade public uses that are occupied at night; keep edges open and accessible.

Examples: Toronto Dominion Centre, Commerce Court

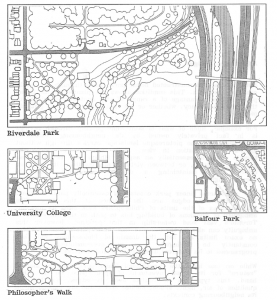

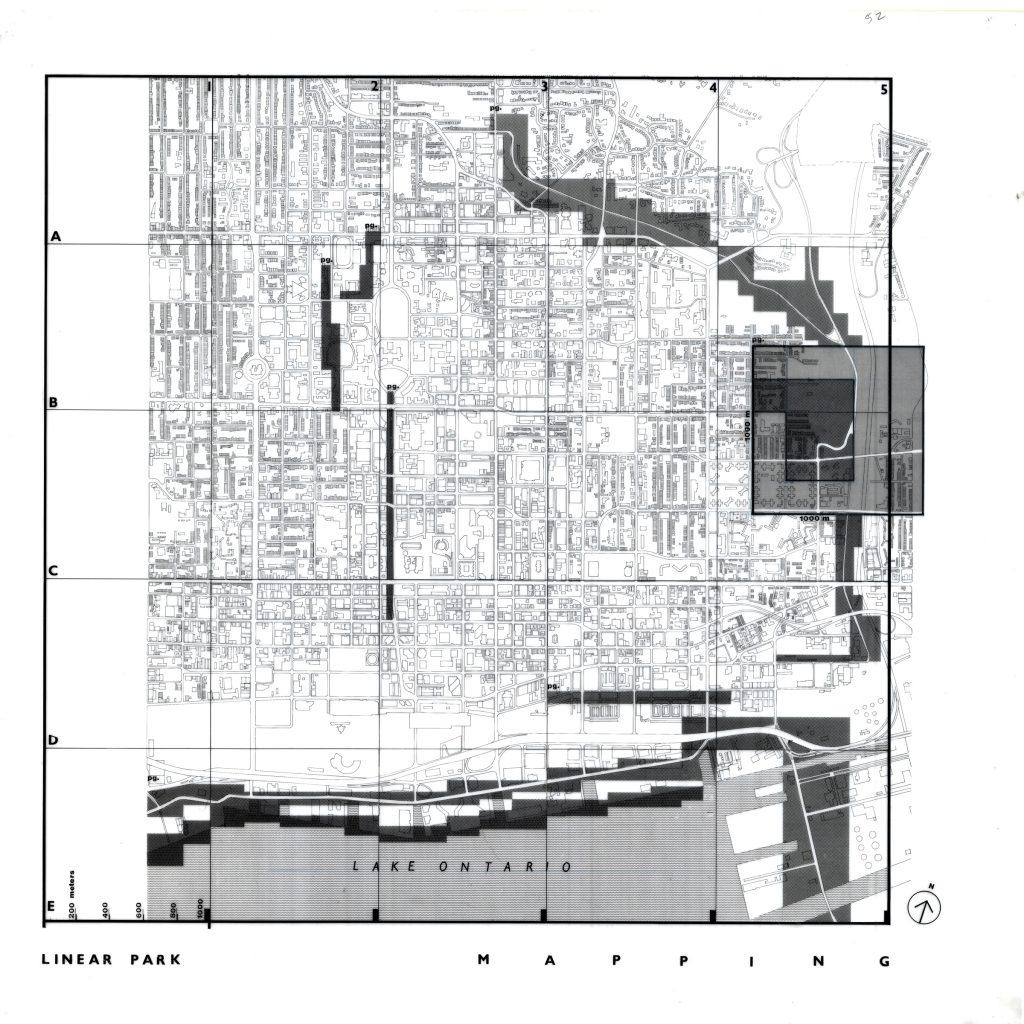

Linear Parks

The linear park is a type of continuous open space that moves through and may be independent of the rationalized city grid. Linear parks provide sometimes dynamic, sometimes retreating counter routes to the normal movement along the city streets. Movement becomes the primary aspect of the linear park. The space is experienced by movement through it, by walking, by jogging, and by cycling. The linear park is subdivided into two distinct categories: the natural system linear park and the constructed linear park.

The linear park is a type of continuous open space that moves through and may be independent of the rationalized city grid. Linear parks provide sometimes dynamic, sometimes retreating counter routes to the normal movement along the city streets. Movement becomes the primary aspect of the linear park. The space is experienced by movement through it, by walking, by jogging, and by cycling. The linear park is subdivided into two distinct categories: the natural system linear park and the constructed linear park.

The Natural System Linear Park

Definition: A continuous open space that moves independently of the city grad, following a natural landform, i.e., ravine, creek, water’s edge.

Location: Natural landforms like water’s edges, ravines, creeks.

Size: Varies; irregular width, expansive length.

Use: Walks, jogging, picnics.

System: The linear park can connect a series of urban parks along its length.

Other: Provide a clear system of repeating ways out of the linear park with emergency phones and good lighting.

Examples: Riverdale Park, Harbourfront, Beaches Boardwalk

The Constructed Linear Park

Definition: A man-made secondary system of movement that travels through the city grid.

Location: Varies; can form connections between larger open space types.

Size: Narrow in width, unlimited in length.

Use: promenade, jogging, cycling.

System: The linear park can link other larger open space types through the city and should begin and end at other larger open spaces areas.

Other: Keep the route of the linear system within easy access of public streets, not running through isolated areas. The linear route should begin and end in public places or larger types of open space.

Examples: Martin Goodman bicycle trail, Philosopher’s Walk

A third type of linear park system potentially exists, but is buried in the submerged Toronto Creeks, like Garrison Creek and Taddle Creek. The traces of these buried systems can be traced through an informal system of small lot parks, and school yards and present many opportunities to the open space planners of the city for further elaboration.

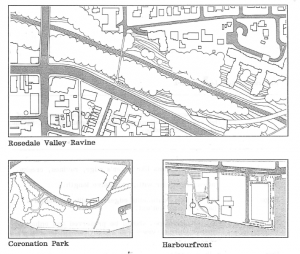

Urban Parks

Definition: a large public open space that occupies an area of at least one city block.

Location: found around natural features, i.e. the ravine, creek; often forms a boundary to several distinct neighbourhoods.

Size: the largest open space in the downtown core; it normally occupies a minimum equivalent area of four city blocks.

Landscape: a balance between paved areas and natural settings to promote regular and urban uses. The natural setting and landforms should be enhanced but not at the expense of having unsafe isolated areas.

Use: casual use, passing through, secondary pedestrian routes, recreational sports, community centres, festivals, playgrounds, pools.

System: the urban parks can be linked together through the creek systems by smaller components, i.e., linear parks, lot parks, forecourts, etc.

Other: provide legible access to public routes and streets, provide high levels of lighting.

Examples: Trinity Bellwoods Park, Queen’s Park, the Grange Park

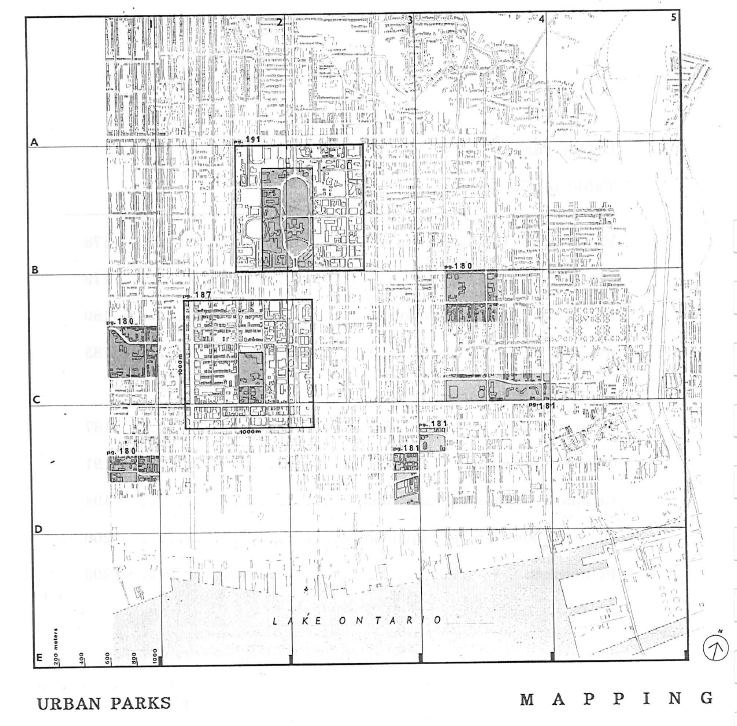

Metropolitan Parks

Definition: an open space of “grand dimensions” whose users come from a more regional area.

Location: forms a limit to the downtown core; often is located at a major natural element.

Size: the largest type of Toronto’s open spaces; comparable to the size of a normal city neighbourhood.

Landscape: the planning of the park should allow for the intermediary zone between the city and the park. Major public routes should travel through the park to promote constant use and occupation. Movement systems should clearly connect into public routes. The scale of the park permits a full range of public facilities.

Use: large scale activities like exhibitions, amusement attractions, sports fields mixed with individual pursuits, and casual use. Planning should allow the use of the park by both large formal gatherings and individuals.

System: the metropolitan park can be the initiator or destination of an open space system established in the downtown core of the city.

Other: all routes should connect clearly to major public systems that run through the park. Built facilities should be designed to provide phone booths, lighting and emergency help.

Examples: High Park, Algonquin Island

Excerpt:

The city is a place that is made and transformed by a process that involves political, economic and architectural considerations. It is ultimately a ground where ideas and thoughts are transformed into public places and structures of the city, or what is called the urban public realm: the street, the square, the park, the market, the arena. This common ground is the means by which cities are understood, through which the city communicates and establishes its nature and civilization.

These public works, of open spaces and built spaces, form the structure of the city. While functioning as distinct autonomous pieces, with their own internal orders and natures, they are also nonetheless read simultaneously as fragments of a larger totality. The character and identity of the city can be witnessed both through the autonomous natures of its fragments, and the dialogue that occurs through the relationship of the fragments to the whole. The city is made and confirmed by architectural and urbanistic practices that can be interpreted through the manner in which buildings, streets and public spaces relate to one another in defining the public realm.

Both built form and open space are understood as a collection of types, a term that allows a categorization according to common shared characteristics. These general types are shared across many cities, though each city tends to have its own morphological and characteristic “rules” that temper the type to be somewhat particular to its origin.

For example, the typical semi-detached single family house of Toronto single family house of Toronto can be called a type: [characteristics: side hall with single run stair, three rooms both ground and second floors, two room third floor, light front and back faces, displacement at middle room for light source]. This type occurs across the city, across a span of one hundred years. It is result of a lot structure that find its origin in the very first act of the Town of York survey, the economics of land development, and the derivation of the traditional English model that has been transported to Toronto and transformed to suit its new host.

In a similar manner, a typology of open spaces in the city exists. However, this system of open space types has not been clearly defined or generally understood. The open spaces of the city were once a well understood framework, an accepted and agreed upon codification of types, and a mutually acceptable means of thinking about the form of the city, in additions and in enhancements. The late absence of the understanding of the roles and natures of the city’s open space endangers the priceless commodity of the public space of the city through their loss of meaning and perceived value.

By classifying the different types of open spaces, and by identifying existing systems and potential new ones, this study proposes that the public open spaces of the city can be recognized and in some cases improved upon as important entities of the city’s infrastructure and worthy of the best quality of design and development.’

— ‘An Introduction to Typology’, from “The Open Spaces of Toronto: A Classification,” Brown and Storey Architects, 1991.